Glider varios are all derivatives (pun intended) of the original aviation vertical speed indicator, also known as the "rate of climb" instrument. The basic VSI is a simple instrument, connected only to the aircraft external static pressure source which provides a reading proportional to altitude above sea level, and give the reading you'd expect, i.e. how fast you are climbing or descending.

The basic vertical speed indicator is pretty much useless for soaring as the absolute up and down movements of the plane are dominated by your movement of the joystick so effectively you're watching a gauge that tells you how far forwards or back you've pulled the stick. For thermal air movement you want to somehow subtract your short-term movement of the controls, and that is what the compensation in glider varios is designed to do. Nevertheless, the default 'vario' in aviation simulators has a long history of having zero or broken compensation.

A comment on units: Aircraft speed display is usually knots (i.e. nautical miles per hour) or kilometers per hour. For vertical speed the instrument may use knots, 100's of feet per minute, or meters per second. I.e. the subtlety here is that different units may be used for speeds in different directions, although conveniently 100 feet per minute is ~1 knot or ~.5 meter/second.

IMHO, if you program instrument software, the only sensible approach is use SI units thoughout, i.e. meters per second for speed, meters for distances including height, and seconds for time.

This section is the key concept of glider variometers - the extensions below for 'netto' and 'speed-to-fly' are relatively simple if you understand total energy.

For a glider in still air flying at a steady speed a basic VSI will show some descent rate, e.g. at 50 knots the VSI might show a sink rate of 1 knot. For a glider pilot that steady sink rate is a crucial indication of energy loss. Note that in the 'still air, steady flight' case, a TE vario will read the same as a VSI.

Note that a glider contains two forms of energy:

For a soaring pilot that exchange of energy is totally irrelevant. It is only the actual energy losses that the pilot cares about. In the absence of drag a pilot could dive from 2000 feet to 1000 feet, then back up to 2000 feet and be back at the same speed and height they were before.

A pilot is familiar with interpreting the steady-state sink rate as an indication of energy loss (to the extent they don't even think about it). So here is the key concept:

Can the VSI be designed in a way such that total energy losses during diving or climbing can be represented on the needle in an exactly proportional way to the energy losses being shown as sink rate during steady flight?

The answer is of course "yes" and the method is to add an adjustment (or compensation) to the rate-of-climb needle if the glider's speed is changing. I.e. if the glider is accelerating that represents an increase in energy which can be added to the needle, and vice-versa if it's decelerating.

A glider in still air will only accelerate when it's descending (and vice-versa) so this positive acceleration compensation will act to move the sinking needle back towards zero. A TE indication in still air should always be negative (think about it). The most dramatic effect of the compensation is the needle no longer swings up and down wildly as you push-pull the stick, as mostly the short-term height losses will be compensated for by an increase in the speed of the glider, and vice versa.

There are clever pneumatic implementations of TE varios which have rearward-facing pitot nozzles to create a compensation to the static air pressure delta driving the instrument, but in competition varios and in simulators the calculation is done in real-time in a computer, with the math explained below.

Potential energy due to height of glider = m * g * h

where m = mass of glider (kg), g = gravitational constant (9.81), h = height (meters)

Kinetic energy = m * v2/2

where v = speed of glider (m/s)

Rate of potential energy change during ascent/descent = m * g * (h2 - h1) / t

where h1 = start height (m), h2 = end height (m), t = time (seconds beween glider at h1 and h2)

Similarly rate of energy change during acceleration/deceleration = m * (v22 - v12)/(2 * t)

So total energy change is m * g * (h2 - h1) / t + m * (v22 - v12)/(2 * t)

Now assume steady flying in still air (i.e. no change of speed) then the second term will be zero and the energy loss is resulting from the height change only i.e. m * g * (h2 - h1) / t. Note that is m * g * (basic climb rate).

This tells you that the VSI needle showing "basic climb rate" can also be interpreted as showing "(rate of potential energy change) / (m * g)". If we divide "rate of kinetic energy change" by the same amount, then this energy change can be represented on the needle in the same proportion as the potential energy change such that the needle now displays both energy changes represented as an equivalent sink rate.

Hence the "total energy" sink rate to display on the instrument is (basic sink rate) + (rate of kinetic energy change divided by (m * g)). I.e.

TE vario reading = (h2 - h1) / t + m * (v22 - v12)/(2 * t * m * g), simplified to:

A Netto Vario reading is simply the TE reading with the polar curve sink rate removed. This can be thought of as an additional layer of 'compensation' to the TE instrument reading. So in still air, at a speed of 50 knots your glider may have a normal sink rate of 1 knot, in which case a Netto Vario will remove this 'polar' sink of 1 knot from the vario reading (i.e. add 1 knot). If the polar says the glider has a sink rate of 2.5 knots when flying at 100 knots, then at that speed the Netto Vario will add 2.5 knots to the TE reading.

The consequence is that in still air the Netto Vario will mostly read zero, regardless of the speed the pilot is flying. Even in still air, the Netto Vario will show sink whenever the pilot flies less than optimally, e.g. if the airbrakes are open, in a sideslip, or with the wrong flap setting for the speed. A real competition Netto Vario must be told the current level of water ballast (ballast isn't usually metered) for it to compute the correct polar, but in a simulator this can be automatic if required.

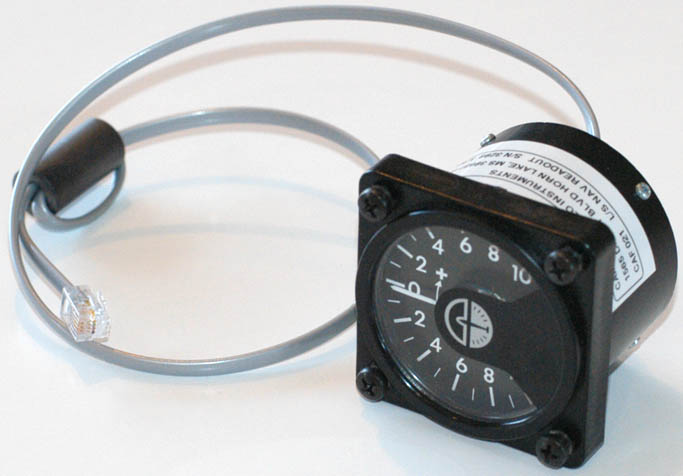

Quite often the Netto Vario on a glider panel will be a smaller (57mm) secondary instrument, while the 'main' 80mm vario is showing Speed-To-Fly.

The speed you fly a glider around a cross-country course depends on the strength of the thermals. If you expect thermals to be strong then you should fly fast between thermals. If thermals are expected to be weak then you should fly more slowly and conserve altitude so you need to climb less. This optimal flying speed to progress through the airmass is unaffected by the wind (but there are considerations as you approach upwind/downwind turnpoints).

In general, in referring to the TE or Netto reading on a variometer the pilot is generally minded to speed up in sink, and slow down in lift to achieve the optimal cross-country travel. A conservative pilot may slow down to best-glide in any lift, to milk the last drop of energy from the sky, but in this case they will not make the fastest possible progress around the course.

You tell the STF vario the strength of the thermals you're expecting - this is referred to as the MacCready setting, e.g. you might dial-in 3 knots. Using your glider polar curve the computer will calculate the optimal speed to fly between these thermals. It will then effectively shift the nominal 'zero' point for the vario to represent the sink rate you'd expect at this speed in still air such that a beeping 'lift' indication is absolutely telling the pilot to slow down, while a 'burp' is telling the pilot to speed up.

For comparison, a TE vario would be giving a continuous 'burp' if you were sinking at 2 knots while cruising in still air between thermals at (say) 80 knots even though you should probably speed up if you are expecting string thermals.

Speed-to-fly varios usually automatically switch back into 'TE' mode when you circle in a thermal.

An excellent article on 'speed-to-fly' theory is Flying Faster by John Cochrane [2017].

Given the data sources required by a modern STF vario, combined with inexpensive position reporting from a GPS the computer can calculate the expected arrival height at the next waypoint or the finish airport.

The calculation will use a GPS for position and will have calculated the wind (e.g. from drift in thermals or the vectors of airspeed and groundspeed). The computer vario will use the input MacCready setting to determine intended cruise airspeed, calculate the wind-adjusted glideslope using the polar, and use the current altitude to calculate the expected altitude at the destination.

Neither the pilot nor the instruments have any real foresight of the lift and sink to be encountered forwards on the journey, so in practice the glider will proceed to do a little better or worse than the calculation and the pilot learns through experience how much safety margin is required in different circumstances. The indication that you will arrive with 50 feet to spare, and seeing that indication trending upwards, is very helpful to the pilot.

It is common on the final leg of a competition task for pilots to set off on final glide even though the arrival height calculation is still negative - they will have assessed the conditions as being sufficiently strong that they will be able to dolphin through thermals and make up the energy deficit.