Do not attempt to land the glider while carrying ballast.

You and the glider will probably survive the landing but the stresses on the wings will exceed the limits of the aircraft.

Flying with ballast is conceptually simple - in strong conditions carry a lot, in weak conditions don't.

For a long time, high-performance gliders have benefitted from an ability to carry additional weight which can be dumped if the soaring conditions become weak. Aviation regulations permit pilots to eject three things out of aircraft:

For various practical reasons, water is the modern choice for dumpable ballast and the ASG29 can carry 200 liters (i.e. 200Kg) of water, adding approximately 50% to the all-up weight of the aircraft to a max of 600Kg. We usually refer to the wing loading of an aircraft (i.e. weight / wing area) rather than simply the weight as this value is then comparable between different aircraft, with an ASK21 maximum wing loading of 33Kg/m^2 being less than the ASG29 minimum, and the fully-ballasted maximum for the ASG29 is 57Kg/m^2 which is exceptionally high.

The conventional expectation is that a 'high wing loading' aircraft will feel most comfortable flying in a straight line at high speed but will feel aerodynamically cumbersome at low speed and in tight turns. In contrast a 'low wing loading' aircraft will feel light, agile and maneuverable at low speeds but will spectacularly fail to accelerate when you push the nose down. Glider pilots used to ridge soaring in a heavily ballasted glider will describe an unballasted glider as feeling "like its tail is tied to a tree". Early-time pilots used to lightweight training gliders will be shocked at how unmaneuverable a fully ballasted glider can be, particularly during the ground run of an aerotow.

A remarkable achievement of the ASG29 design is that it remains flyable at every corner of the flaps and ballast envelope, across a very high range of speed and wing loading.

The use of ballast exploits the following unexpected fact of glider aerodynamics:

When weight is added to a glider, the aircraft will both sink faster and also glide faster, and in general sink speed and airspeed will alter in the same ratio.

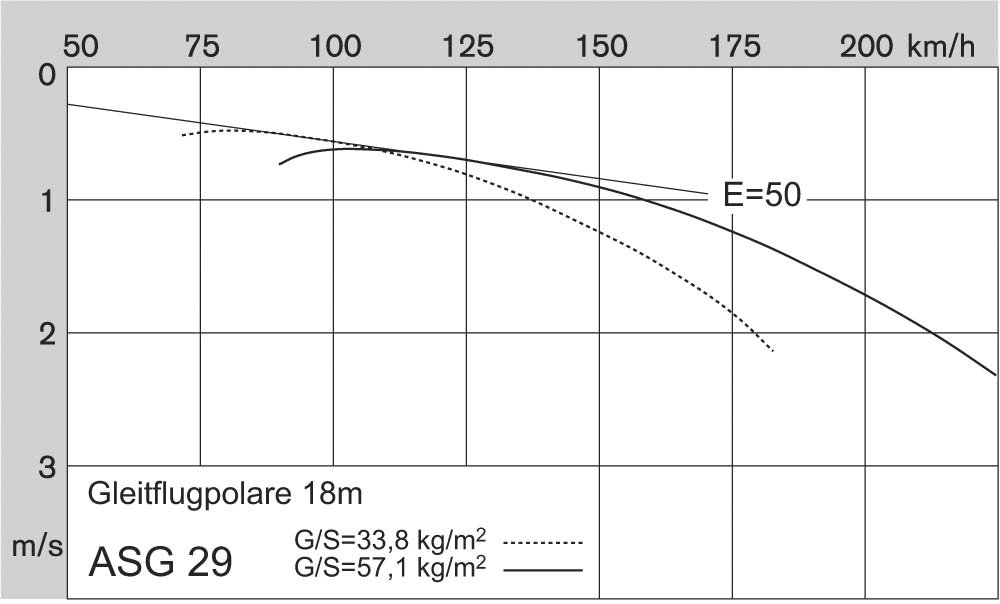

This means that the best glide ratio is effectively the same at different levels of ballast. However, the heavier the glider, the faster speed at which best glide is achieved. The effect is illustrated in the ASG29 polar diagram (of airspeed vs. sink) for the min and max wing-loadings with similar best glide at 100km/h and 125km/h respectively (54 knots and 67 knots). The ASG29 absolute best glide is achieved in flap setting '1' with approx 50% ballast.

The rest of this guide will refer to the ASG29 ballast as 0%..100%, as this is how it is displayed in the on-panel indicator. 100% equates to 200 liters / 200Kg of water ballast.

The ballast indicator is on the lower right of the panel:

X-Plane commands are available if you prefer to set a joystick button or key to control the fill and dump valve open / close.

On the ground, the ASG29_B21 will default to starting with 25% ballast. The glider can then be filled with

ballast by clicking the  icon, at which point the indicator will

read 100% as above. You cannot fill the ballast while in the air...

icon, at which point the indicator will

read 100% as above. You cannot fill the ballast while in the air...

The OPEN and CLOSE buttons on the ballast indicator control the dump valve.

From full, the ballast takes 4 minutes to dump. This means on a fast straight glide to the airfield you will begin dumping 15km / 9 miles away. (At 150kph / 80 knots the distance would be 10km / 6 miles).

For a partial dump of the ballast, simply OPEN the dump valve until the indicator shows the required amount and then CLOSE it again.

Be aware that any ballast on board will make the glider more difficult to handle during the ground run. A cross-wind will be particularly problematic.

You can make life considerably easier by launching with a headwind blowing straight down the runway.

It would be relatively unusual to winch launch the ASG29 at all as it is an expensive aircraft, and even more unlikely to carry water ballast during a winch launch. The problem is the relatively high risk of a launch failure, when the ballast would make the ASG29 more difficult to handle and you have zero chance of dumping the ballast before landing.

The X-Plane default of 25% ballast is probably the maximum reasonable for a winch launch in the ASG-29.

Flap setting 4/A or 5/T should be used for a winch launch.

Full ballast can be safely carried on an aerotow launch although the glider will be considerably more difficult to control than without ballast, with less aileron control and a ground loop more likely.

If the launch is aborted then the glider is far more likely to pitch onto its nose during braking, as the ballast is carried well above the point of braking friction and also the center-of-mass of the glider is moved forward as a result of carrying ballast.

Flap setting 4/A should be used for Aerotow launch.

Just keep in mind the appropriate speed-to-fly will be consistently faster if you're carrying ballast. For example, the ASG-29 will achieve its best glide ratio at 70 knots / 125 kph when fully ballasted, and if you encounter any sink the vario will push you to fly considerably faster. As part of your familiarization with the ASG-29, you should watch the 'speed-to-fly bug' move around the rim of the ASI when you fill or empty your ballast (and also as you adjust the Maccready setting) - you may be surprised at just how quickly you're expected to fly compared to a training glider like the ASK-21 or a wooden glider like the K6.

Energy you gain by 'dolphin flying' (aggressively pulling up in any lift you encounter) pays massive dividends in a high performance heavily ballasted glider and it is often possible to fly long distances without turning at all. The alternative, i.e. circling in thermals (see below), is adversely impacted by carrying water ballast so you want to avoid it as much as possible.

As you slow down from a fast cruise, work your way through the positive flap settings. A fully ballasted ASG-29 in negative flap (setting '1') will handle like a dying fish below about 60 knots (110 kph) and you should be in flap setting '3' or '4/A'. If you turn into a thermal then '5T' or '6T' should be promptly selected.

In general, a fully ballasted glider will thermal really badly. The plane will be heavy and unmaneuverable and you cannot expect to fly the aircraft slowly to get the most out of the thermal as you would if the ballast were empty. X-Plane is kind to ASG-29 pilots as the thermals tend to be large and even, so the advantages a lightweight low wing-loading K6 would have in the hands of a skillful pilot are diminished.

The best technique in a heavily ballasted ASG-29 is to get into flaps 6T, ease the trim back, and establish a smooth stable circle at 50-55knots (~100kph) requiring the minimum of control input, and try and keep in the core of the thermal without rapid changes.

Use the climb averager on the Computer Vario to learn the true climb rate you are achieving in thermals, and set the Maccready setting accordingly, while considering whether your water ballast is worth carrying.

Note there is quite a big difference in handling and performance between full ballast and 50%. If you find yourself thermalling more often than you expected, or the climbs you are getting are weaker than you were hoping for, then dump at least some of the ballast. In reality that almost guarantees the thermals will be absolutely record-breaking all the way around the rest of the course.

Of course you can only dump the ballast once, so pilots naturally hang on to ballast in the fond hope that conditions will improve or at least your next thermal will be a better one. In RL soaring there's a careful strategy of suffering a bit with heavy ballast at the start of a race, preparing for expected stronger conditions in the middle of the day. Also it is common (at least in the UK) for part of the course to be in claggy or weak conditions which you need to survive to possibly enjoy strong conditions and a fast run on the way home afterwards.